28 November 2022

AUTHOR:

BRANDON STOSUY

EDITOR:

ANNA BULBROOK

Public record

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group on continual evolution

"When Chim↑Pom formed in 2005, there weren't other collectives in Japan, and there wasn't this definition of a “collective.” The word itself didn't really exist. People thought it was a rare thing because, at the time, it was more the climate where there were individual artists like Makoto Aida or Takashi Murakami. … But looking back at the more general history of Japanese art, you can see there actually were a lot of collectives in the past."

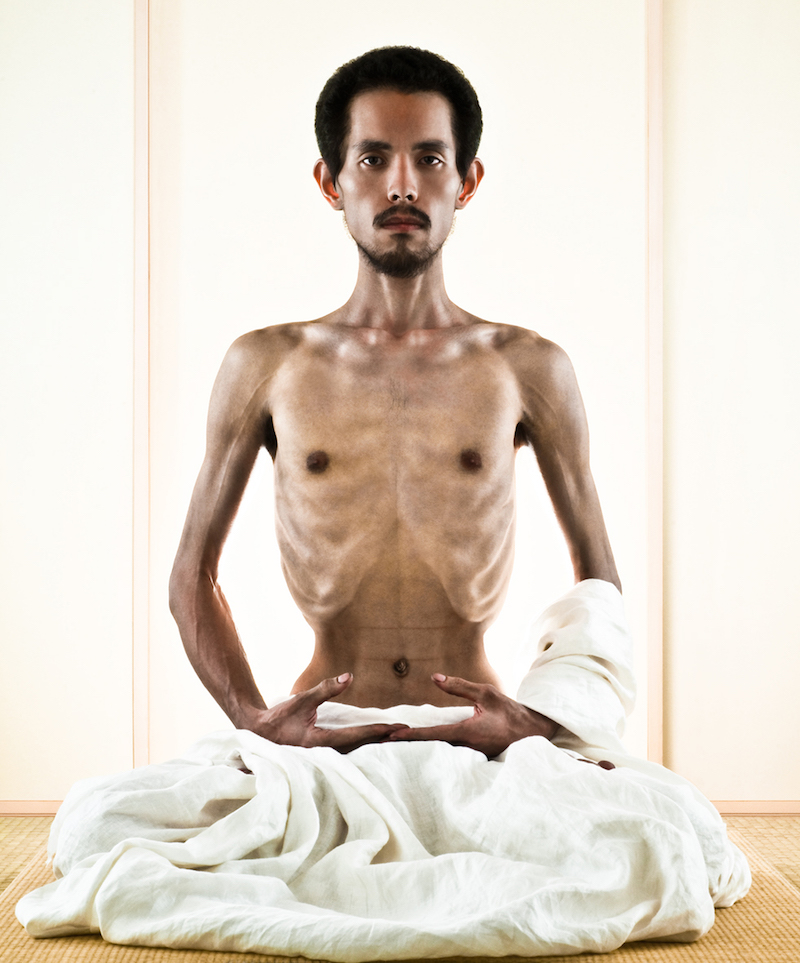

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group; Photo by Seiha Yamaguchi

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group is an expansive multi-media artist collective that formed in 2005 in Tokyo. The group consists of Ryuta Ushiro, Yasutaka Hayashi, Ellie, Masataka Okada, Motomu Inaoka, and Toshinori Mizuno. They work across materials and approaches, but tie their practice together conceptually. As they put it: “Responding instinctively to the ‘real’ of their times, Chim↑Pom has continuously released works that intervene in contemporary society with strong social messages.”

I first met the members of Chim↑Pom in 2017. I was in Tokyo as part of a zine project for the website I co-founded and interviewed the group in a live setting with my friend Ryu Takahashi translating. (In April 2022, they changed their name from Chim↑Pom to Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group.)

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group has continued to morph and expand and shift since we met in person, existing in and (literally) creating their own space(s). Over the last few years, I corresponded here/there with one of the members, Ryuta Ushiro. Most recently, he’d wanted to see photos documenting a live series I’ve been curating with the artist Matthew Barney for the past decade and change. (We share the idea of the event as art.)

When Yancey and I first spoke about Metalabel, I thought of Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group as a great example of the kind of collaborative system highlighted by the project. Here's a conversation with Ryuta and his translator and collaborator Hibiki Mizuno.

How did Chim↑Pom start and how did you decide to do it as a collaborative group project?

Chim↑Pom met through this artist Makoto Aida who represented the subcultural scene along with this other artist, Takashi Murakami. In Japan there were these two big artists that were representing this subcultural scene in the contemporary art world in an interesting way.

Takashi Murakami had a system where he would welcome younger people in, but it was in more of a factory style, and there was a very clear top-down structure in how he would mentor younger people. Makoto Aida, the person Chim↑Pom met through, had no system. There were just a bunch of these younger people, younger artists, or not just artists, but people that would gather around him.

I started to invite other people to join this loose group. There were around 30 people drinking and hanging out. Through that, we were able to form Chim↑Pom. First it started out with me and these other members, Yasutaka Hayashi, and Ellie, who at the time was a model for Makoto Aida.

MEMBERS

Ryuta Ushiro, Yasutaka Hayashi, Ellie, Masataka Okada, Motomu Inaoka, and Toshinori Mizuno

Key Releases

Super Rat (2006)

REAL TIMES (2011)

Don’t Follow the Wind (2015)

The other side (2016)

Garter (artist-run space)

Background

Founded in Tokyo in 2005, Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group is an artist collective whose work engages in social critique of the contemporary world and investigates the self-described “‘real’ of their times.” The group frequently explore topics of everyday life in this work, filtering their thought-provoking commentary through a prism of popular cultural references, playfulness, and a sly sense of humor. The specific subjects considered by Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group vary widely, from urbanization to consumerism to borders, and more. A consistent throughline is a focus on themes of infection, contamination, and contagion. Their piece Super Rat (2006), which features rats that the group captured in Tokyo, stuffed, and painted to resemble a Pikachu, is named for the poison-resistant rats that proliferate in major cities, and calls attention to the persistent chemical contamination which humans are unwillingly exposed to in daily life. Likewise, their collaborative exhibition Don’t Follow The Wind (2015) is located inside the Fukushima nuclear exclusion zone, making it physically inaccessible for the public to visit, and draws further attention to the ways in which humans have poisoned the planet, creating new borders in the process. The group has gained international acclaim for their releases, and collaborate widely, including opening and curating their own artist-run space Garter in Tokyo, where they shine light on the work of their contemporaries. In April 2022, they changed their name from Chim↑Pom to Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group.

Purpose

To produce and release artwork which directly responds to and critiques the conditions and structural organization of modern society, often through direct public intervention.

What's been the value of having it be a collaboration versus just going it alone?

When Chim↑Pom formed in 2005, there weren't other collectives in Japan, and there wasn't this definition of a “collective.” The word itself didn't really exist. People thought it was a rare thing because, at the time, it was more the climate where there were individual artists like Makoto Aida or Takashi Murakami. That was the norm. Everyone thought we would disappear within a year or so.

But looking back at the more general history of Japanese art, you can see there actually were a lot of collectives in the past, and there were different group exhibitions and different attempts to create an art industry of its own separate from the Western context. For me, doing something always meant collaborating with other people. It was just a natural inclination that we had.

Don't Follow The Wind, our ongoing project in Fukushima, the northeastern part of Japan, is also about working with other people and collaborating. If we do projects in different areas of the city — for example, this area in Tokyo called Kabukichō, where it's a distinct red light district — we work with the people who work there. We did a big retrospective at the Mori Art Museum and had to work very closely with the museum staff in order to make it happen.

When you collaborate with people, it's not like you always work with people that understand what you mean or that are on the same page with you. A lot of the time you don't share a common understanding or a common ground. For example, when we work with people on Don't Follow The Wind, we don't always share the same language of art with the people there, and so we have to really build our relationship on other things besides art.

"The Pussy of Tokyo," 2017; Photo: Kenji Morita

"When you collaborate with people, it's not like you always work with people that understand what you mean or that are on the same page with you."

Can you recall the first action or artifact that you were inspired to create together as a group?

One of the first things that we tried out was to go to a batting cage where you can go and bat for a long time in this area, Kabukichō. We tried to film a couple of videos there because we didn't really have the skills. We didn't go to art school, so we don't have the kind of knowledge that usual artists have. We were thinking about how we could do something, and at the time, we just had a video camera. It was a time when YouTube was emerging, so we did a lot of different stunts. We would try to get into the coin lockers and do a bunch of different foolish things, but they were not really working. At the same time, we were thinking, “Okay, so maybe we do really need to approach this in an artistic way instead of just doing anything.”

Then we started to focus on [one of Chim↑Pom’s founders] Ellie and how she lived her life. There's this term in Japanese “Gal,” like G-A-L, and it's basically a kind of fashion subculture that deviates from traditional modes of femininity; women who don't care what other people think and live their life freely in a strong-headed way. She was living this mad life where she was going out a lot and doing whatever she wanted, and so we tried to merge our artistic perspective with her distinct lifestyle. Through that, we made our first work, which is called Erigero which means, “Ellie Vomits” in Japanese. It's a video piece where Ellie is drinking this pink fluid and then vomiting it at the same time. That became our initial work.

When we filmed that we sensed this artistic god falling upon us. We thought it was a great work and Makoto Aida also agreed and so he helped us show the work for this exhibition where pink was the theme. It was curated by this Bauhaus curator. He showed this work to the curator who became upset about it. They were saying the fact that there's men who are basically prompting and chanting for this women to drink and vomit, that structure was not really favorable in terms of a feminist approach. But, if you look at the video and if you actually watch the end, the structure gets reversed where Ellie is actually leading the whole thing. But they didn't understand that whole context. So that was one of our first works where we showed the Erigero piece along with our well-known Super Rat project.

After the initial showing, we stopped presenting Erigero for a while because we thought it was too radical. We just felt like people weren't able to fully understand it. But then for this year's retrospective at the Mori Art Museum, we showed it for the first time in more than 10 years, and actually it became quite a trend on TikTok. There were a lot of teens and people in their '20s that were resonating with the work. I thought that was interesting — this cyclical return to this work after a long time.

Does Chim↑Pom have a mission statement?

It's not really a mission statement, but it's a way to live our life. A big concept that runs throughout our work the idea of the Super Rat. Super Rat serves as the background to all of our practice and all of our work. It's this idea of being fed poison, but using that as a nutrition to continue to transform and continue to mutate and change ourselves. In that way, we are constantly changing and we easily get bored. We’re not really an artist group that's able to do the same thing over the course of many years, like the artist Yoshitomo Nara, who's very known for just consistently doing certain kinds of paintings over his entire career. We're not like that.

As people, we're all very different. Each of us have our own inclinations and interests and everything, and we're not really unified as a whole. We’re constantly adapting to whatever changes that are happening to the environment. Super Rat is about the relationship between the environment and life and how to survive in certain situations. You can also see it in different communities that we've worked with in the past, like the atomic bomb survivors, the A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima, the different group organizations that have been working so hard and passing down the narrative.

You can see that with the Mexican slum community that we worked with on the Border project, the other side. You can see that with the Fukushima survivors of the nuclear power plant accident and tsunami. It’s this idea of responding positively to really devastating situations or situations where you're being fed poison and how you positively are able to adapt and mutate and respond to that kind of situation.

"SUPER RAT," Diorama Shinjuku, 2016; Photo: Kenji Morita

"Super Rat serves as the background to all of our practice and all of our work. It's this idea of being fed poison, but using that as a nutrition to continue to transform and continue to mutate and change ourselves."

How do you define a project as being successful or not successful?

It’s difficult to just define or offer a clear formula. I think there are several different patterns of how we define or measure success. A good work isn't created from just following the idea that we initially have, like a music score and just even if you have a really clearly mapped out idea, just following that idea doesn't always necessarily lead to a good work. There's different detours that you take within the creation process, and whenever there's changes within that process, it usually leads to a good project.

For example, when we did the Mexico border project, the very day when we were going to cross the border and place one of the art objects that we had prepared to do a shoot for the project, we had an LA Times journalist that was accompanying us for that day. Ellie was very upset with me that we had a third person that was joining us on this very day, because for her, it was this really important ritual that we were doing with the team that we had created, which was the family that we were working with at the border. And we had formed this team called Team Libertad, and so for Ellie, it was really important that this was a ritual that we would do just as the team and to not have a third person joining us.

I think it's about maintaining this sense of ritual within us that you can also see in the Erigero, the Ellie vomit video as well, where we're not really taking into consideration what other people might think of us, because when we try to respond earnestly to what is being asked of us of a particular time, the works tend to become too easy to understand.

Another element that usually leads to a good project is meeting the key people, really the crucial person that brings the project together wherever we go to in different locations. So that, for example, will be the main mother that was taking care of her family in Tijuana, where we did the Mexican border project, or that may be one of the leaders of the A-bomb survivor groups, this person called Mr. Tsuboi, or it might be the survivors of the tsunami and earthquake in the Fukushima area for Don't Follow the Wind. There's always these key people that we work with for each project that really guide us through.

What are the most important tools for your work, the things that you need to make a project?

The physical body, and use of video have always been one of our initial tools because we didn't have other skill sets. Another thing is thinking about cities and public space as tools to see how we can place performances and how we respond to this kind of space. We see the public space as a tool, a place where we can stage our videos. And so as an extension of the body, we also use tools like writing in the sky, using airplanes, hiring pilots to write in the sky for example. Another tool that we use is parties.

A usual artist would create sculptural pieces, for example, and display them at an exhibition, and that would be the flow of their project, and that would just be the end of it. But for us, we're always thinking about how we can make the process more real. So, for example, we have this very big sculptural project called Build-Burger, where essentially we used an entire building and we cut the floors and layered them like a sandwich, like a burger. In that work, the building itself is the tool rather than the act of cutting, because the act of cutting, we can just ask industry professionals to cut the concrete and to create the layers. But for us, the building itself is the tool. And then on top of that, we hosted different parties in the building. So that goes hand in hand with the sculptural piece. They're not separate.

For us, that's really important because we like to create situations and we like people to actually use the space. For a more conventional artist, just creating the Build-Burger sculpture would be enough. For us, we always want that added element of creating a situation. And usually that'll be for some kind of event or some kind of party.

The culmination of the experiment of working in the public space has led to our project Street where we literally create actual streets in different spaces. And so, from starting off as individuals intervening into public space, we became people that actually created a new kind of public space. Even then, whenever we create this public space, we think it's important that individual activities are taking place there otherwise it's not really interesting to just create a public space. At the same time, Chim↑Pom hasn't just been working on opening up public space; we’ve also been doing the opposite where we also create spaces that are almost a rat's nest or something. For the Manchester International Festival, we did a project where we worked in an abandoned tunnel under the subway station. And so there's also these certain areas that we work with that are not explicitly open to the public or very much out in the open that you have to really dig and you have to really get into it to understand or look inside of it.

How do you finance the projects?

We fund our projects by selling our works, but before that, when we weren't able to do that, we thought of different creative ways to gather funds. One example is when we did an exhibition at the Maruki Museum in 2011 that was focusing on our projects in Hiroshima and Fukushima. Toshinori Mizuno, our Chim↑Pom collective member, went to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. After the radiation accident, he went there to work there for several months, and he donated all of the money he made by working there for the exhibition. For our banners and pamphlets, we had the byline supported by TEPCO, the company. That was an interesting twist because it's literally an exhibition about radiation and nuclear energy, about Fukushima, and it's supported and technically funded by TEPCO.

Another example of our funding system is basically for the retrospective for the Mori Art Museum this year we also needed to gather funds. And so we were trying to gather funds from this company called Smappa!Group, a group which is actually Ellie's husband's company. It's in the Kabukichō nightlife district so the museum basically rejected any funds from this company. Because of that, we decided we were going to change our name.

So now we're not just Chim↑Pom but we're actually called Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group, the name of the company. We did that as an option to show that we are always changing, and we're always mutating, like in this Super Rat sense, we're constantly adapting to our environment. That was an example where this issue of funding and gathering money and also our concept all came together.

Right now, we are actually thinking of different projects that we can do as Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group rather than Chim↑Pom and so in that way, we're constantly thinking of evolving.

How do you support a project and want this out in the world? I know if you're working with the museum, maybe the museum has a catalog or promotes it, but in general, how do you try to get the word out about what you're doing and keep it going and make sure people see it?

The exhibition format is our main way to maintain and put out the project into the world. Through exhibitions, we're able to connect with people of different cultures, different races, different locations, everything. There's a way that people really connect through exhibitions.

We also think very positively whenever the exhibition format is collected by museums or different institutions, because once we're in a collection — a museum collection or a different art institution collection — we're able to pass that work down to the future audience. That adds a whole other layer of dynamic factors.

Often the projects we do are very site-specific, and they focus on a particular community in a particular location. By doing an exhibition, we can connect those people with audiences from all over the world. We also have a lot of books. We've published about nine books at this point, and we do parties and events.

If I were to ask you to think about maybe the highest high, the greatest moment in the life of the project, is there a moment that jumps out to you?

The highest of the highs are usually when we're able to create. We're able to really realize a project that we thought was not realistic or we thought was not possible. The moment when a plan that was really difficult, that people didn't think would be able to happen, becomes okay, becomes realistic, becomes an actual reality — and that moment when we're able to really overcome whatever hurdle to make it happen is always the highest of the highs. It’s usually when we're working with a specific community and we've been negotiating with them for a long time, but then maybe something happens and something clicks and they're able to say, "Okay, yeah, let's do this." And so that's what often happens within the actual creative process. There's two elements to the process. There's the ritual aspect, which is more internal, which is us creating the work. And then there's the presentation format when we're exhibiting and we're showing it to an audience.

And then to answer the opposite question of the lowest moments, the parts that aren't fun are actually the Chim↑Pom meetings. They are very long. Often whenever we're stuck in these long meetings, we have to come up with a really brilliant idea that'll help us push forward and in an almost impossible situation in order to get to that next point. So they're really tedious, and we often get into petty fights. So, the lowest of the low is definitely when we get into these long, dragged out meetings, and then maybe one member doesn't get along with another one. Things just get all muddled and complicated.

My last question is just to complete this sentence, "Doing it all over again, I would..."

One thing that we would want to do it again or do in a different way is to be more cognizant of mental health. One member, Toshinori Mizuno, who moved from Tokyo to Hiroshima, who is no longer part the meetings because he has a different job in Hiroshima, was very physically active in our group where he would be open to doing anything, getting tattoos in his body, doing all kinds of very radical physical acts for the group. He became quite exhausted from doing all of the really more hardcore elements.

At that time, the collective was also in a good place in our career, and we wanted more things out of it. We weren't really able to listen to him as much about his needs or what he was going through. The things that we did weren't exactly the most considerate things. For example, we would go to his house, and we would literally light up fireworks there. He was very much, "This is too much. You've gone overboard." And we would be like, "Oh, why are you reacting that way? You're able to handle this kind of thing." And that was always our dynamic and always our interactions. Since then, we've been able to maintain a really good relationship. So, all in all, it turned out well, but if we were to do it again, it would've been better to have been kinder.