02 November 2022

AUTHOR:

YANCEY STRICKLER

EDITOR:

BRANDON STOSUY

Public record

Why the Wide Awakes are one of the world's most interesting metalabels

A conversation with the Wide Awakes about their origins, their practices, and the decisions and nondecisions that led to their collaboration

The origins of Metalabel began with a group called the Wide Awakes. In 2020, I got a text from a friend, the artist Hank Willis Thomas: “Come join this thing I’m doing,” he wrote. “Be you and be a part of it.”

The text confused me. Hank is a celebrated artist. What could I offer him? I ended up passing on the invitation because of the uncertainty and my own self-doubts.

It didn’t take me long to regret this decision.

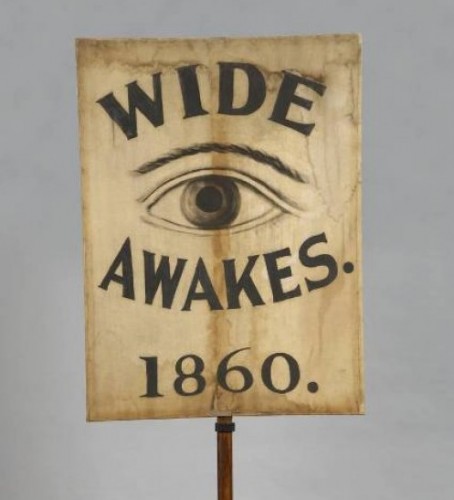

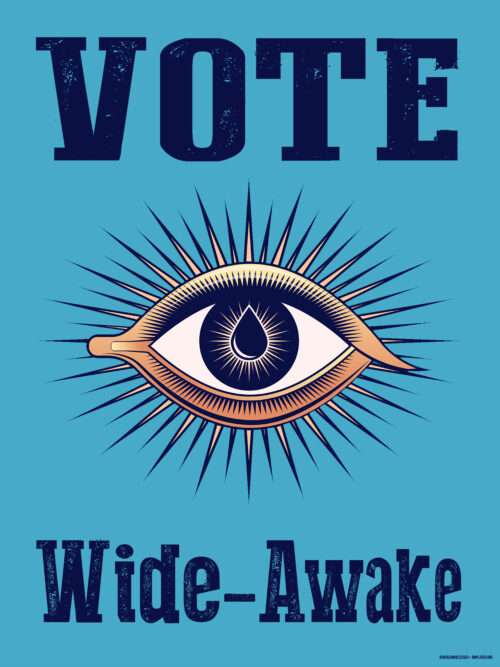

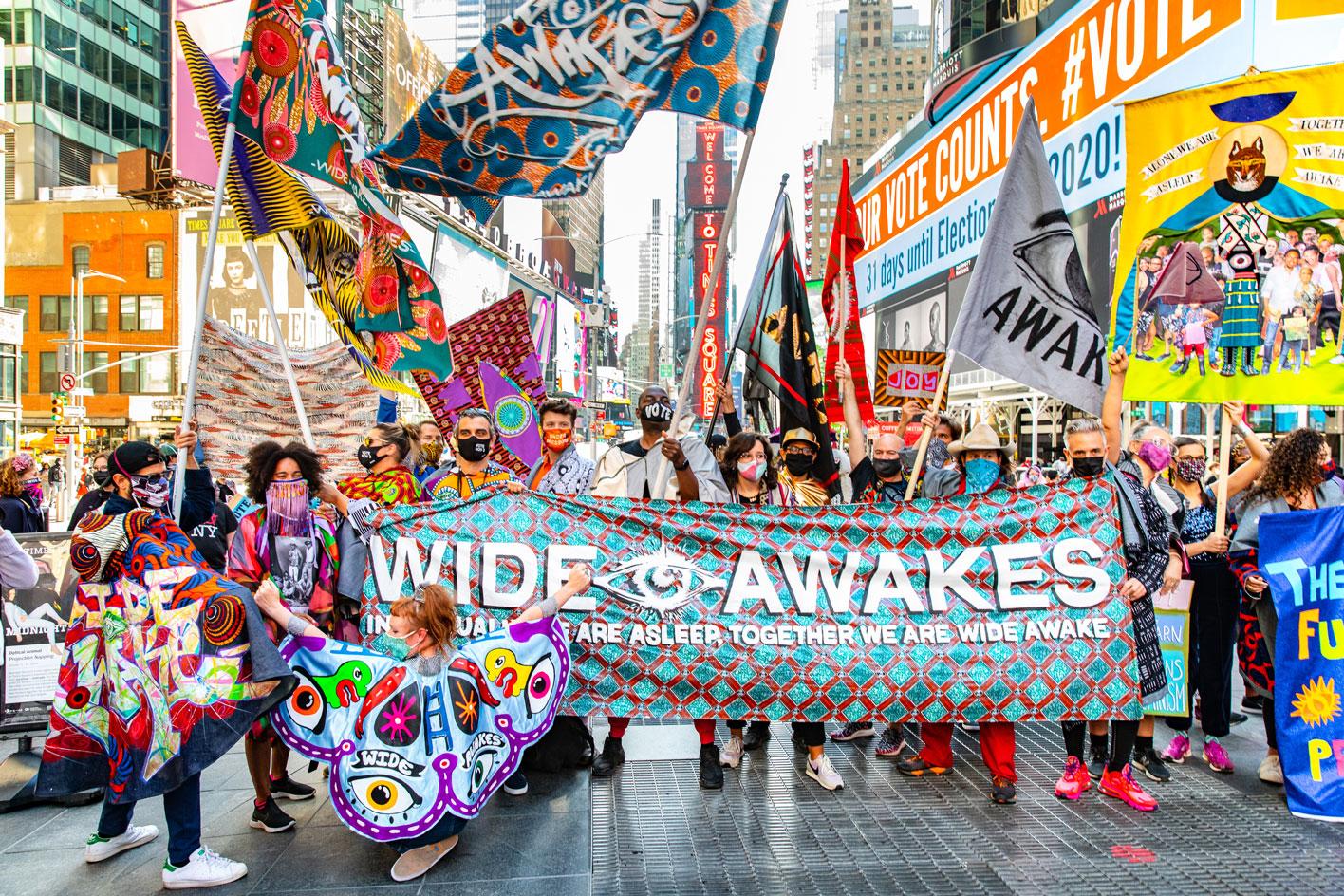

In the year that followed I watched as the Wide Awakes dropped a series of creative actions and works across culture inspired by the name and look of an 1860 group of activists called the Wide Awakes, who were part of the movement to end slavery in America.

The modern version of the Wide Awakes created colorful protests, community-led moments, and collaborative works that shared an intention of bringing people together and helping them become “wide awake.” The actions sent tremors across the media and culture.

In early 2022, Public Record sat down with a dozen members of the Wide Awakes to explore how they got started and what they’ve learned building a very metalabel modern movement. Walking away from this conversation we were convinced: the Wide Awakes are one of the world's most interesting metalabels.

How did the Wide Awakes begin?

ERIC GOTTESMAN: Everybody has their own entry point into what happened. My own relationship to it started a few days after the 2016 election, when several of us were in South Africa. I remember getting a text from Hank about the Wide Awakes, which I know he had looked into before that. Between 2016 and 2020 there was an idea percolating about the 1860 Wide Awakes and the mythology around it.

Do you remember the gist of that 2016 text?

ERIC: It was probably a Wikipedia page. [laughs] Carly probably has the best insight into that question.

CARLY FISCHER: My relationship began by chance. Hank and I bumped into one another, and he was like, "Come to the studio. I think I have something for you.” I got there and all of a sudden I was in the midst of a conversation that I had no pre-empting for. I thought we were going to maybe talk about a project I might want to work on, but instead the project began before the conversation about it did. That was the nature of the building of the Wide Awakes in general.

Hank was trying to rally the people that have been collaborators in different ways — with For Freedoms, with his studio, in his personal life — building a community that in some ways already existed informally. The invitation was vague. It was like, “Come to the studio at this time,” without any context about what the conversation was going to be. Eric has described it as “a suspension of disbelief.” This feeling that if you were willing to show up without enough information to go on, we were willing to dive into a project that we didn't understand what it was going to be.

It was an opportunity for people to gather and connect with one another, talk about what they were working on, what they were passionate about, what their aspirations for a better world would be, figuring out our points of intersection with one another and how that could be an opportunity to build community.

"We're all working towards better futures, more equitable futures…"

What was the first action that energy got translated into?

ANYA AYOUNG CHEE: The first public manifestation of the Wide Awakes manifested as what we call a band, which is a street activation in costume, at Carnival in Trinidad. My memory of it is that Eragan called me to talk about designing capes inspired by the Wide Awakes — story capes. I had some vision around the relationship between the six original Wide Awakes, who guarded Cassius Clay, and this vision is of the moko jumbies that represent the spirit guardians of our Carnival who crossed the Atlantic from Africa to Trinidad and are a traditional Mass character in Trinidad. When we were in Trinidad for Carnival, it felt like the right moment to activate what is now this celebration of joy as a form of resistance through this communal celebration. There was this marriage of symbolism between the original Wide Awakes and how we celebrate Carnival.

In terms of how it became an actual decision: I don't know if it was a decision to be honest with you. We were all ready to activate this thing, we were together, we had the opportunity to make these capes, and we did it. We just did it, and whoever was around participated. It was all colliding at the same time.

When you began to meet in the studio and have people in to talk about what they were inspired by and what they cared about, how did that reach some unified statement, or some expression of, “Here is what brings us together”?

HANK WILLIS THOMAS: Everyone had the same feeling, which is, “What does he want me to do? What is he asking? Where’s this going?” People are still in different spaces of these kinds of conversations, where it feels like there are circular, unproductive conversations, but there's something there.

I can talk about my own experience, which was that I realized I have been blessed with an incredible life surrounded by incredible people. Not only had I not really woken up to that fact, I told myself that most of them hadn't woken up to that either: how blessed and how incredible we are, and how we are living in probably the best moment in time in history. At the edge of the cliff, with all the information and all the power at our fingertips, and we spend our time distracted, investing in things that make us angry and afraid, rather than connecting with each other, either in person or through those same devices, around the things that make us feel happy and strong.

I feel happiest and strongest when I'm in community with people and they're willing to be in community with me. Not that we agree or that we like each other, but that we're actually choosing to connect around this idea that joy and power come from investment in oneself, but also in our surroundings. I was frantically calling all these people around me to be like, “Hey, let's just be together, have you thought about what would happen?” Remembering random things different people had said once upon a time, saying, “Why about that thing you said?” They're like, “What are you talking about? Why are you making me say this in front of people?” “Because that was amazing!”

"[We're] at the edge of the cliff, with all the information and all the power at our fingertips, and we instead spend our time distracted, investing in things that make us angry and afraid, rather than connecting with each other, either in person or through those same devices, around the things that make us feel happy and strong."

If you think back to those first conversations, were there any decisions or ideas that especially shaped the project?

PATTON HINDLE: I’m laughing because decisions are non-decisions. In the early days we were trying to think about the infrastructure of the organization, the collective. We kept trying to find ways to create labs for creative work, but also how that lab could access resources within the larger collective to produce what it is that they were thinking about. But where finance comes into that, the really boring but basic stuff that you need, there were things that we tried various ways to form and I don't think we ever really resolved.

ERIC: It felt more like a lot of people throwing a lot of spaghetti at the wall and then some pieces of spaghetti stuck around for longer and some just fell down. [laughs] There were four or five mission statement attempts from different people. All of them were great, but none of them were all-encompassing.

The record label is an elegant analogy, because when record labels work best is when they're allowing artists to make the work that they're already making. Something that was happening a lot in the conversations was like, “Oh, this has already been happening for the 10 years or 15 years or 30 years that we've all been collectively doing our work, and we're just now recognizing that it's all converging in this moment.” There were onramps, whether it's things people already mentioned — the capes and the WhatsApp groups that were happening for communication, the public events — that were ways to access and to commune.

CARLY: Everything felt like a call and response. We just kept trying stuff. Some stuff people liked, and some stuff people hated. The only way to make sense of if something was gonna work or not was to put it out there, because if we kept trying to make a decision it never happened. It required someone to just try something and then see how people felt about it. We put something out there, and some people liked it, some people didn't, but the thing that was useful about it was that it was a starting point. Once it existed, there was an opportunity for people to riff on it in new ways. We just had to find a way to start.

HANK: How we launched was Jose — and I don't know who else, maybe somebody else here — made this mission statement and then posted it to social media, and then there was a whole like, “Alright, I guess we're doing this.” [laughs] They just announced it. At its best: a person makes a decision and those who are in whatever collective just join them.

ANYA: I was just going to mention that: decentralized social media management.

ERIC: I think that idea came from you, Huey, because you said at NatGeo a lot of photographers do that. But a lot of these platforms are set up for everybody to stay in their lane. There's a filtering of these decisions into the thing. Whoever “we" is, nobody really knew everything that was going on.

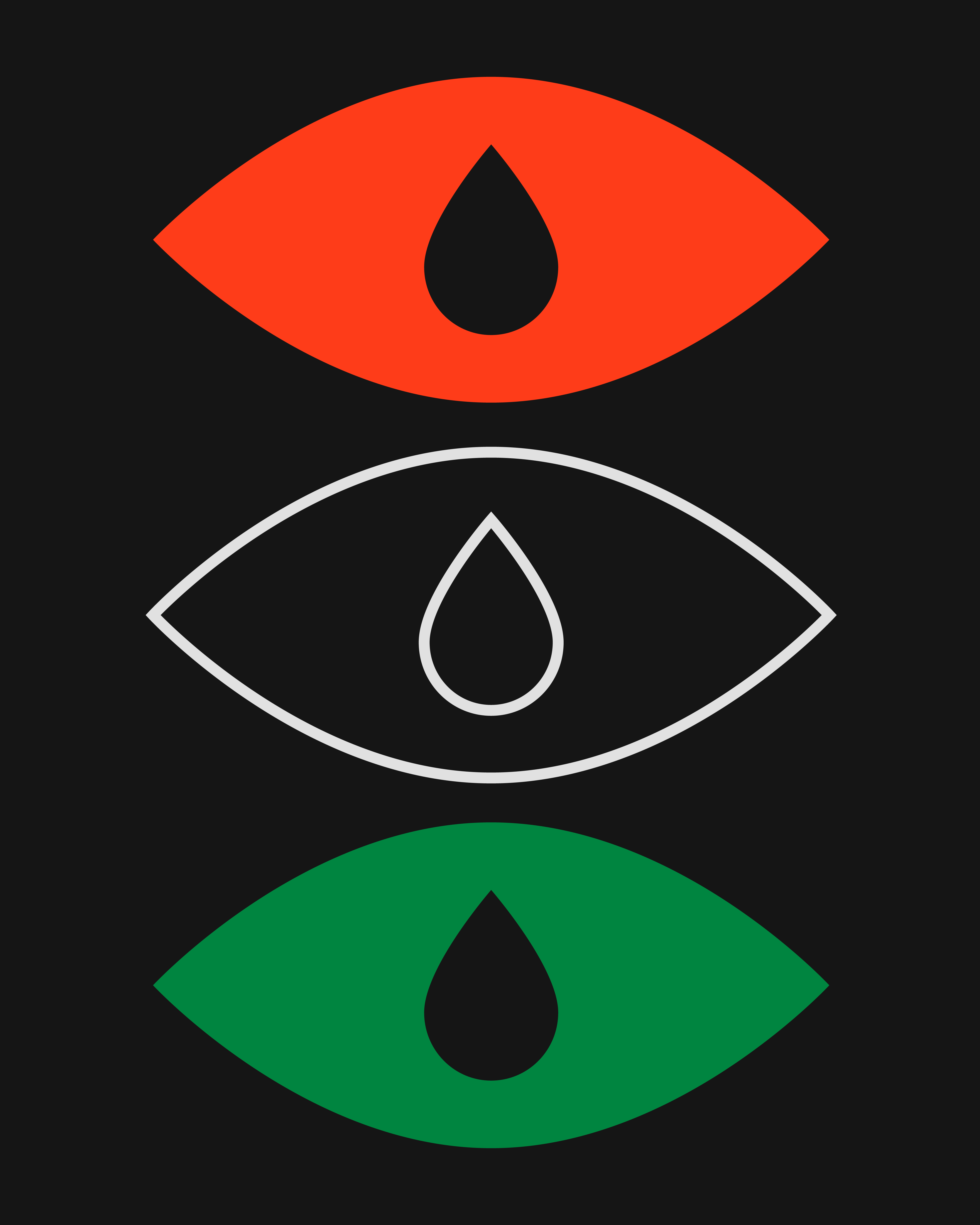

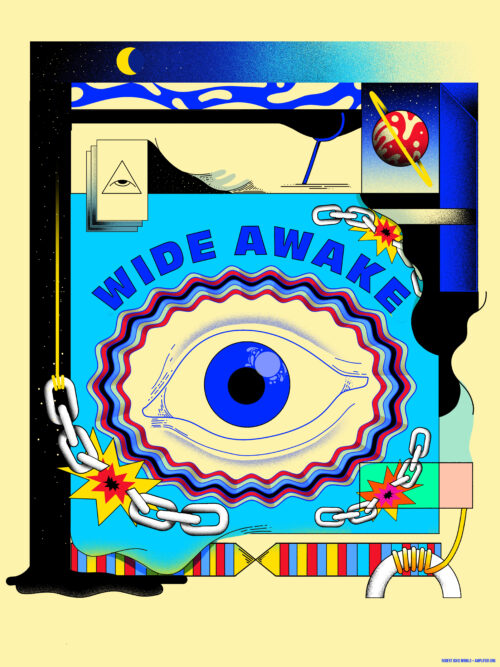

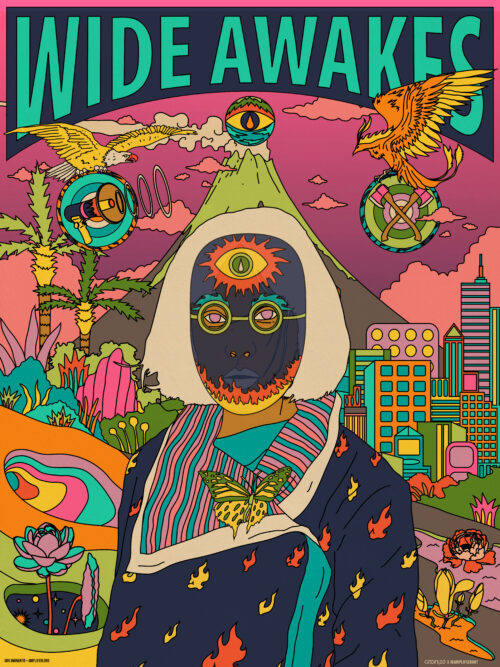

AARON HUEY: Instagram was a way to sketch so that we didn't get stuck with a particular slogan or identity. If somebody didn't like an eye, they could put a new eye in and say “Here's another one." It was like launching a new album. But I was like, “I don't want a fucking graphic designed eye by a fucking graphic design agency.” So I just started making 100 different eyes because I thought it was bullshit to hire graphic designers.

KIARA BENN: One thing that does go with Instagram, if it's posted in the universal WhatsApp chat and someone's like “How do I get this on Instagram,” it will make it to Instagram. If you don't have a login, it's still open to everyone because it will make it on there.

ERIC: The platforms are built in such a way so it is supposed to be one person having it. It's interesting how we're reusing Facebook’s same platforms, but to collectively source into something that looks like it's a funnel or something like that. It'd be cool if there were a platform that could do that more naturally.

"We put something out there, and some people liked it, some people didn't, but the thing that was useful about it was that it was a starting point. Once it existed, there was an opportunity for people to riff on it in new ways. We just had to find a way to start."

MEMBERS

Hank Willis Thomas, Aaron Huey, Cleo Barnett, Jenny Holzer, Elliott Walker, Tim Hucklesby, Lauri Freedman, Fiana Keleta, Carly Fischer, Eric Gottesman, Claudia Peña, Manushka Magloire, Shepard Fairey, Luca Piccin, Kiara Benn, Wyatt Gallery, Gina Belafonte, Nour Batyne, Anya Ayoung Chee, José Parlá, Marsha Reid, Michele Pred, Cassils, rafa esparza, Coby Kennedy, Patton Hindle, and more.

Key Releases

Wide Awakes Day: An annual day when the Wide Awakes gather in parades and marches to celebrate their work together.

Carnival: The first event where their energy was put into action, as one member took the lead on a project in Trinidad

Cape making: Creating a practice and visual emblem of how they create their identity in the Wide Awakes

Open source toolkit: They turned their entire framework into an open source toolkit where anyone can be a Wide Awake

Background

The Wide Awakes are an open source, artist-led movement that brings together a wide range of creative collectives in support of political and creative action. Their name comes from an 1860s group called the Wide Awakes who led the abolitionist movement to end slavery in the US who wore colorful capes and used distinctive colors to show their membership, a practice the contemporary Wide Awakes have adopted as well.

Purpose

To radically reimagine the future through creative collaboration.

The internet is geared towards single player mode. It's all built around an individual controlling things. Everything is individualized. Most technical systems are built around the concept of an individual user. But a lot of projects now, it doesn't make sense to think about it as being individually led.

ERIC: There's a translation issue from existing systems to potential systems. There's an ethic that's grown up in the Wide Awakes, which is, “Everybody, just go and do your thing." At the same time, sometimes the story that's being told—if, for instance, For Freedoms does something, does that mean that it's a sub-project of For Freedoms? That kind of concern has come up. Really, it's just that For Freedoms has the mechanism, the bank account, the legal entity. But the way the story is told then determines if there's funding involved, who gets what credit, and so that gets a little messy because there isn't the structural thing that allows for this multiple authorship, multiple ownership. This feels like a conversation we've tried to have a bunch of times and figured out multiple solutions.

ANYA: No matter how idealistically we want to create the mechanism for collective ownership, it still seems to come down to this centralized ownership issue or centralized responsibility of governance.

How does money work within the Wide Awakes?

CARLY: Not that well. There is a translation error between our imagination for new systems and the reality of current systems. We have not solved what it means for us to have communal monies to work with. In the meantime, we use For Freedoms as a fiscal sponsor, essentially, and they become the administrative support. But I don't think anyone feels like that's a long term solution.

Let's talk about metalabels.

A metalabel is a group of people who create a collective identity for a shared purpose, and they express that purpose through public releases. I'll share a graph I made cribbing from a Bauhaus illustration from the 1930s to visualize the structure.

I wanted to talk through what these spaces are for you as the Wide Awakes starting with "Purpose." What is the central force that's gathering this group of people together?

NOUR BATYNE: It's better futures. It’s as simple as that. We're all working towards better futures, more equitable futures. All the various iterations of the mission statement, that's really at the core of it. We exist within a multiplicity of futures. We are in collective, we live within various futures in this moment.

CARLY: I agree with this multiplicity of features, but rather than “better,” I would say liberated futures.

NOUR: Liberated, yes.

Going back to the metalabel structure, who was invited to be a part of the squad? Can a member of the Wide Awakes invite anyone else to join?

HANK: I’m motivated by the idea of de-tribalization. One of the themes we've worked with in For Freedoms is “us and them.” They are us and we are them. Us is them and they are us. Everyone I’ve reached out to, it’s like, “You are a person I've looked up to in one way shape or form, you've inspired me to be a bigger, better, greater version of myself. I would love for you to add yourself to the rest of us, who are also pretty friggin' awesome and also still in need of support in living in our full awesome power.” A common thread I had was generosity. People who, in their work, had also been centered around “What can I give?” instead of “what can I take?” Those were things that I thought were my desires for inclusion.

ANYA: The only thing that really, formally describes belonging is being in a WhatsApp group. But does that really define you as being a Wide Awake? Could you be living as a Wide Awake in your work and in your life, and you don't even know about the Wide Awakes—how do you define all of that? Are you a Wide Awake sometimes, and then sometimes you're not? Because you’re not actually living always in this principle of living awake. It's more of an acknowledgement of a way of living and showing up that may come and go. The definition of community and criteria of invitation is really more in the context of how you invite people into their higher self, how do you invite them into a way of being that is the highest vibration?

What are the releases you're most proud of and what qualifies as a release?

HANK: I’ll do my top five. Carnival, definitely a top five. Juneteenth was a top five, Wide Awakes Day top five, and Wide Awakes Maybe Day top five—the mobile soup kitchen was at a lot of those things. The disorientations. Especially the energy of, “Hey, just throw in a link,” and everyone shows up.

CARLY: The first celebrations in summer 2020, like Juneteenth and Interdependence Day, that helped us build a language around what live events could be in the context of the uprisings that were happening in the moment. That led us to October 3 as Wide Awakes Day, which feels really key to me. Also the open source branding was something that we could release and offer as an invitation to the community to iterate upon. Everything that came after that could go out into the world and feel almost like a finished product, but actually it was really a starting point. Everything is an invitation for you to reinterpret.

ERIC: The word “release” makes it feel like it's held and then released to the public. That doesn’t describe my interpretation of the different events that happened, or came up, or spontaneously upsurged, or exploded, or vomited. The word implies a gatekeeping or a holding back that I think is antithetical to the way in which a lot of activities took place. It could benefit from a little bit of that planning, but in its purest form, I feel like it's not exactly the same.

What word would better speak to that?

CARLY: I like activations.

ANYA: The frameworks that allowed for the activations, or whatever you call them, to happen, the cape-making, flag-making — the structures that allowed these frameworks to activate in and of themselves are a public offering that we all shared. Although they're sort of a subset, the capes alone are a public offering. And the communal making of the capes and the framework of how to make the capes, how to make the flags — that's something that Eric was saying that really resonates with me, that the releases were almost the doing of the work itself. In doing the work it was offered to the public, but it's not that there was a separation between the doing of the work and the releasing of it.

Last question: “Doing it all over again, we would __”

CARLY: Make the same mistakes, but probably with more compassion.

NOUR: For me, the way that it unfolded was perfect, and the lessons that were learned along the way needed to happen the way that it did.

WYATT GALLERY: So much of where we are today and the good things that have come and keep coming out of the Wide Awakes come from the path that it’s led, and the ups and downs and the ins and outs. They’ve all contributed. The people involved have a certain sense of family and a certain sense of direction to this future that so many of us want to see. A lot of that involves showing different perspectives, and illuminating different perspectives that most people in this dogmatic culture don't get to see.

That nebulous approach can be difficult for a lot of people to wrap their heads around. But it's specifically that structure that allows us the freedom and elbow room to create and get things out there in the immediate fashion. Two of the foundational structures for what Wide Awakes can be were always the A-Team and the Avengers.

These disparate elements of people that have all of these different skills and all these skills that link up. We come together and we produce and we output, and then at the same time, we all have our own individual movies that go on at the same time. I'm so glad that all of the elements have happened, all the interactions and dynamics have happened since we started this in the way that they have. That’s what led us to this point.