29 September 2022

AUTHOR:

AUSTIN ROBEY

EDITOR:

BRANDON STOSUY

Public record

Ellen Mara De Wachter: art worlds and collaboration

In 2017, Ellen Mara De Wachter’s book Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration was published by Phaidon. It’s a book highlighting the working dynamic and creative processes of 25 artist duos and collectives. The author spoke with us on the topic of collaboration in the art world and beyond.

“The lone heroic genius is a concept that increasingly doesn't hold up to scrutiny. And that's something that people who work collaboratively know.”

What’s your background? What led you to create this book?

I studied theory and philosophy, and then I went to work in galleries. I was working as a curator independently and also in institutions.

I met my partner, Samuel Levack, who is a collaborator in a collaborative art duo with Jennifer Lewandowski. As a writer — because writing is such a solitary, individual activity — I just couldn't imagine how you could do your work with another person. They had been working together at that point for 11 years or 12 years and I was really intrigued to understand what this dynamic was. And then I also started to notice works by different collectives.

I suddenly noticed stuff that's been around for a while, and also, there was a bit of an increase in the visibility of collectives at that time, like at the 2015 Venice Biennale, which had a spike in the number of work by collectives, proportionally.

Art is one among many fields where there are certain taboos still that aren't discussed, and money is one of them. And how you author your work is still one of them, even though there's been a discussion around authorship for decades, or a century, really. But it kind of felt like I wanted to ask people questions about how they create art collaboratively — as artists, and also as humans.

What is the myth of the lone creator? Where does this come from?

The myth of the lone genius comes from ancient civilization. If you go back to ancient Roman civilization, genius was the expression of the male spirit. When it comes to visual art, it is something that comes in around the late Middle Ages, and it is associated with the increase in the financial value of artworks. And that directly related to the single authorship of an artwork.

There's an example I cite in the book, where the contract for the commission of the work stipulated that the author, and only the author, could touch certain parts of the work, even though the work might have been made by a workshop — which was common for most artworks at that point. Different people were part of a workshop. For example, some people had specialisms painting hands or some people had specialisms painting landscapes, and so they would work all together and the master would sign his name, and it would be attributed to him; it was him most often. That has been inherited through hundreds of years of the patriarchal system that we are still subjected to now.

More recent example, in the United States, is the rise of the abstract expressionists and the portrayal of them as heroic figures.

Jackson Pollock and wife Lee Krasner

If you think about Jackson Pollock, working in a solitary way with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, heavy alcoholism, and throwing paint on the floor in a really expressive and powerful way, he incarnates that myth of the lone genius. But the reality is a little different than that. He worked very closely with his wife, Lee Krasner, and she sometimes suggested titles for the works, and they discussed her work. There was a real collaborative activity going on.

Not to mention the fact that Jackson Pollock is part of a larger group of artists experimenting at the time supported by patrons like Peggy Guggenheim. Life Magazine supports him by doing massive features on him, and photographers document him doing his work. So he's not alone all the time.

Howard Becker, a sociologist I refer to in the book, uses the term, “art worlds.” It means that every artwork that we receive is the product of its own unique art world, and that's a combination of people from different fields. It includes everyone from the people working in the factory producing paints, to the people stretching the canvases, to the family of the artists who may be helping them, to the dealer selling their work, to the people cooking their food, and so on. So the lone heroic genius is a concept that increasingly doesn't hold up to scrutiny. And that's something that people who work collaboratively know.

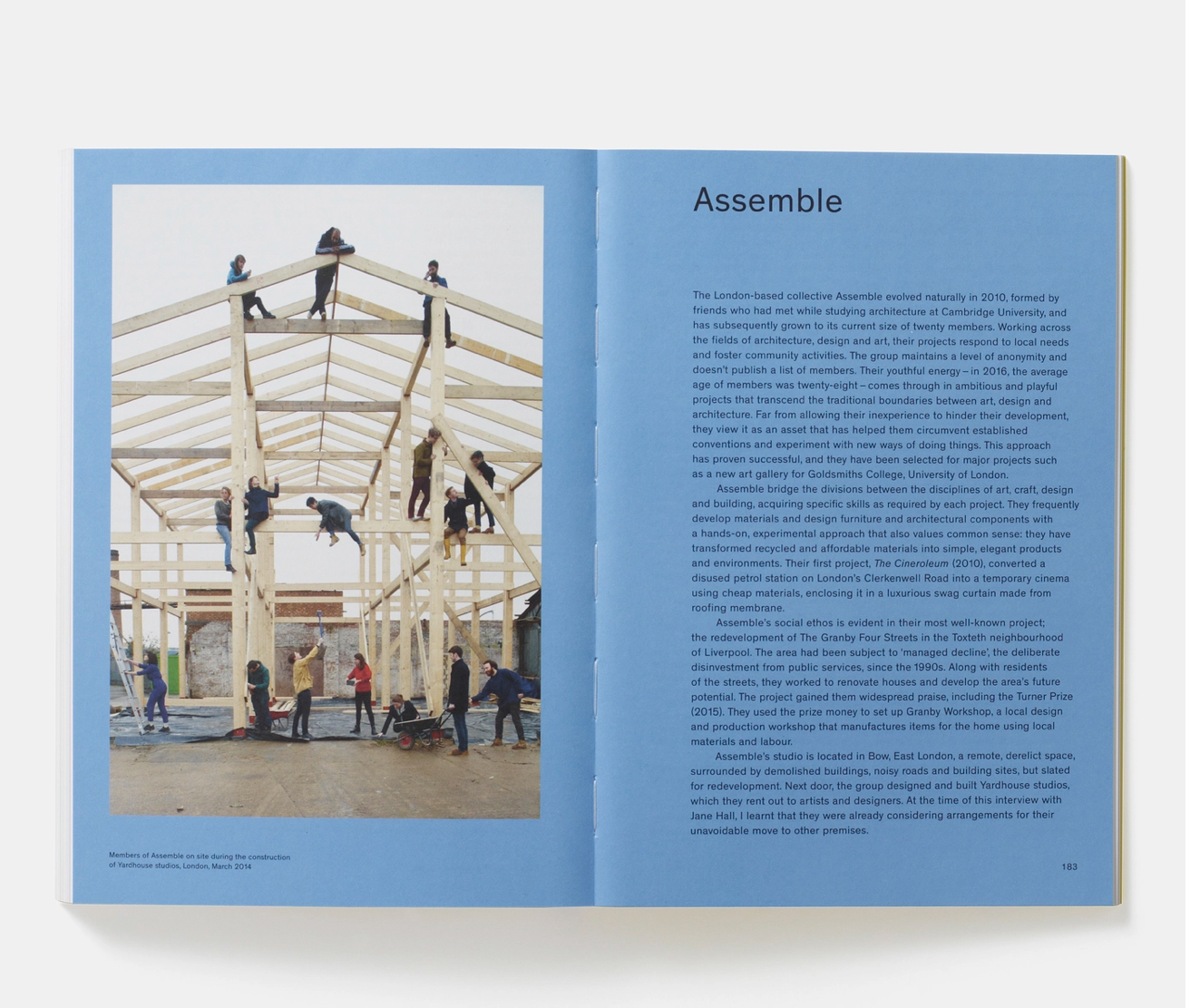

In 2015, the multidisciplinary collective, Assemble, won the Turner Prize. In 2021, the Turner prize shortlisted five groups, all collectives, for the first time. Is this a sign of a shift towards collectivism in the art world?

I don't want to try and predict the future because that's a fool's game. But, what I've noticed is that grassroots ideas and practices appear, reach the mainstream, and then kind of branch out. My hope is that this trend of collectivism in the art world doesn‘t become an anomaly, or a curiosity. Instead, I’d hope that just as often, people would be motivated and inspired to work collectively because they feel that they can, rather than it being something they might feel is too risky.

MEMBERS

16-20 permanent members

Key Releases

Folly For A Flyover

Yardhouse

The Cineroleum

Background

Assemble is a multidisciplinary design collective who operate under collaborative and democratic principles. In 2015, they became the first collective to win the Turner Prize. The jury remarked that Assemble “draws on long traditions of artistic and collective initiatives that experiment in art, design and architecture. In doing so they offer alternative models to how societies can work.”

Purpose

To advance socially responsible placemaking and create community-focused projects with DIY ethics.

What are some benefits of artists working collaboratively?

Conversation, sharing of ideas, deepening of ideas, challenging each other's ideas. I think it's just a fundamental human drive to be gregarious. You know, you can also work in a solitary way, and then have your fun gregariously separate from your work. If I'm looking at the work of the groups profiled in the book, friendship is a central component of it. Many of them are lovers or long term romantic partners. Some of them are ex romantic partners. Some are family siblings. Actually, two are twins. So the benefits are, I think, a more holistic experience of work.

For me, that's an expression of choice that people have chosen to work together. Loyalty, trust, and the fact that they're not bound contractually — they're backed by love of some kind, but that's what I would say is the umbrella motivator in some way. If you walk away from your job, you might be in trouble with the company. But if you walk away from a creative relationship it might be heartbreaking.

Why do you think it might be challenging for some artists to work collaboratively? What would some of the challenges be?

That framing begs the question of whether a creative, artistic process can ever be easy, right? Working on your own is very difficult emotionally, as well. So I don't know that working together is harder than working alone. Working alone, you sometimes only have yourself to talk to, so you have internal conflict, whereas working with others, you can externalize that conflict. That said, there are definitely certain pragmatic challenges from that, that come from working collaboratively.

The art market isn't primed to sell works by collectives for the same reason that we've just discussed around the question of the lone genius. Some people are really sympathetic to work by collaboratives, but that doesn't necessarily translate into a willingness to sell their work or the ability to actually sell it. What that means is that people who work collaboratively operate in a certain sphere, and it doesn't always cross over. If you look at blue-chip artists, they tend not to be collaborative groups. And, that again, traces back to the value that we put on single authorship, and branding. Other collectors or museums also have historically been reticent to acquire work by collectors, because they're not sure of their investment there. They think, “You know, perhaps it's not worth investing in case that group breaks up,” or that it may take them a lot more effort to explain to their audiences.

How do you see younger artists approaching some of these questions of working either as an individual or as a collective?

I’ve noticed a great concern amongst many young artists to make a financial success of their work. That is a real burden for young artists. And I completely understand why they feel that way. There are many reasons, but two big reasons are that it's really expensive to be alive. The other one is that we've just gone through about 40 years of art as a commodity, and I don't know where we're gonna go next.

What I've noticed is that younger artists coming together to create work often organize around an issue. Whether that is an issue around a sense of identity that the people in the group might share, or whether it's an issue of social justice, or a political belief or allegiance. If you look at the groups that were in the Turner Prize, what they were organized around ranged from women's reproductive rights, black and queer identity, or food justice. And these groups had an ability to create work in so many different registers from creating an oyster bed off the coast of mainland Scotland or creating parties and opportunities for catharsis, to different things that supported their shared purpose.

Some of the older artists in the book had a motivation to discuss things that had come before and situate themselves in a lineage of art history. I kind of see that less because I think we're in an emergency in so many different ways that I feel like there might be a perception that that might be slightly less effective now.

"I don't think the collective is served by an erasure of individuality. I think it's essential to be both an individual and part of a group. For collaboration to be sound, there should be an ability to exist both within and without the group—to toggle between and to freely move between."

Do you think we’re entering an age of “post-individualism?”

Yeah, I mean, I guess it's an interesting idea. I don't think the collective is served by an erasure of individuality. I think it's essential to be both an individual and part of a group. For collaboration to be sound, there should be an ability to exist both within and without the group — to toggle between and to freely move between.

I think both are really important. It's definitely the case that our society is mired in supra-individualism, and many civic allegiances are ruptured. It's a mess, but I think historically when there was an attempt to integrate everyone to the nth degree, it's devastating for people as well.

Inaugural Summit, Morschach 2013 #1 by GCC group, a multidisciplinary art collecive

Whose work do you find exciting?

I still find loads of people featured in the book to be exciting.

For example, August Orts, which is a Belgian collective of filmmakers. They're interesting because they don't author works together. They're more of a production and curatorial agency as well as each of them being an individual artist who has their own practice and success, which then feeds back into the group. They've just curated a biennial of Moving Image in Belgium. I haven't been so I can't comment on the content of the biennial, but they're active in ways that are commissioning younger artists, bringing people from different countries together in one exhibition.

I’m currently working on a book about the use of food as a material in art, so I’m especially interested in artists who work with food in one way or another. So, the duo Cooking Sections, who use food as a methodology to ask questions about global systems, including agriculture, economics and geopolitics; or the artist Kathrin Böhm, who is part of several collectives involved in grassroots organizing including the art project/drinks company Company Drinks, the international association of artists MyVillages and the Centre for Plausible Economies. And I always keep an eye on how groups that have been working together for a long time, continue to operate, for example Guerrilla Girls, who refresh and renew their ideas, strategies and membership to keep confronting issues of injustice in the art world and the world at large.

MEMBERS

Members are anonymous.

Key Releases

MoMA protest

Guerrilla Girls Talk Back

Background

The Guerrilla Girls are anonymous artist activists who formed in 1985 when an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, billed as a survey of “the most significant contemporary art in the world,” featured 148 men, 13 women, and no artists of color. After that, this collective of women artists used guerrilla tactics to highlight racial and gender inequity in the art world.

Purpose

To use disruptive headlines, outrageous visuals, and killer statistics to expose gender and ethnic bias and corruption in art, film, politics and pop culture.