To platform or not to platform

That is the question

Last week’s New Creative Era episode covered the topic of technology platforms. When are they beneficial? When are they problematic? How do we as artists relate to them?

As individual artists, creators, and collectors, whether and where to platform is perhaps the key strategic question of our age. Setting aside the politics of which you choose to use and why, how should we as creative people think about when and where we put our work?

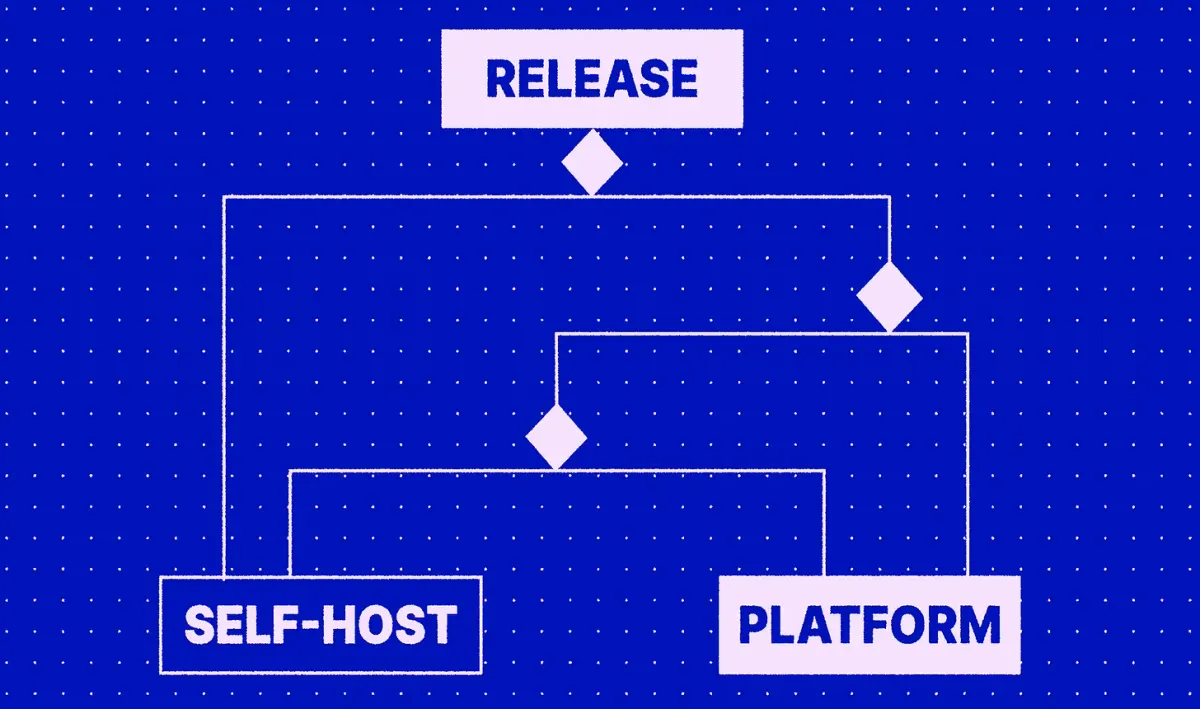

The choices tend to be:

- Publish with a platform, which means access to a well-tested tool and participation in an ecosystem that likely provides some sort of audience and network effects. It sometimes means your work is locked there or people have to create an account to engage with it.

- Homestead in your own spaces that keep your content and context fully under your control. However you are 100% responsible for delivering traffic and technically maintaining your space.

Many people choose to publish with platforms when first starting, then homestead as their clout grows. Others homestead while selectively using platforms to drive traffic to their sites.1 For most it’s a constantly moving target, and one we wrestled with ourselves last week.

The past few years we’ve sent our weekly messages using Substack. By now we have a big archive of essays, interviews, and editorial that spans a wider creative universe. We wanted to better integrate those pieces into Metalabel, so we decided to switch to Ghost, a more white-label email-and-blogging service.

The offerings and tradeoffs of each service are worth noting. Substack is more of a platform, which means there are network effects that have built up over time, and are now growing rapidly. As a platform, Substack’s product offering is more uniform as a way of demonstrating their product, and that others can make newsletters too.

Contrast this with Ghost, a white-label tool that lets you send newsletters and post content under your own brand and identity. In exchange for that autonomy, you lose out on some network effects, as there’s no Ghost platform or destination where people discover one another.

Both provide valuable services. Both have their strengths. Both have their drawbacks.

Last week we tried switching our newsletter from Substack to Ghost, building out a nice site that gave our archive more life. However the first email we sent got seen by far fewer people than normal. Partially because it was coming from a new sender, and partially because it didn’t receive the benefits of network effects.

This left us with a difficult question. What’s more important: fully owning our brand identity or our ideas being exposed to as many people as possible? As you can tell by where this email is being sent today, we made a decision — for now. But it might not be forever.2

What’s important is that we can move back and forth with no real cost beyond our time. Because email addresses are owned by the writer/project and editorial archives are stored in standardized exportable/importable formats, creators in this space have more freedom of movement. This is not true for most non-email Creator Economy systems.

When it comes to deciding where to platform, the key considerations are:

- Audience — Is there a built-in audience or the potential to grow yours by being there?

- Money — Is there a net-income benefit?

- Brand priority — Who does the product make more prominent: the platform or the creator?

- Audience portability — Can you take your audience with you or are they locked in?

- Sunk cost — How time consuming is it to use this new product, and do you have to commit to get value?

- Compatibility — Is it easy or hard to use with your current communications tools?

- Longterm alignment — Is the company and product aligned with your ecosystem or are they focused on a different target audience?

How a platform measures up to each of these questions gives you a sense of how high or low the cost is of trying them — and potentially leaving.

Here’s how Metalabel rates:

- Audience — A small but growing built-in audience: 12,000 collectors, nearly $500,000 spent in past year.

- Money — 10% take rate, no upfront costs. Platform routinely outsells creators’s own sites/Shopify’s. This will get better over time.

- Brand priority — Creator-centric, from using subdomains that put artists first to hyper-minimal brand presence on artist pages.

- Audience portability — Followers and collectors fully exportable.

- Sunk cost — Can use for one-off drops or larger catalogues.

- Compatibility — Simple to use. Don’t have to create an account to support.

- Longterm alignment — A project by creative people for creative people.

This alignment with the needs of the creative community is because we as Metalabel are artists, creators, and collectors ourselves. We’re building what we want.

Our ultimate goal is for Metalabel to bridge the best of both worlds: be a place where you can discover and be discovered, as well as an underlying infrastructure that powers homes of your own.3

That was the beauty of the best of all web2 products: Tumblr. A world of many worlds, independent and interconnected. This is the platform experience many of us continue to yearn for. A way to be ourselves and be part of something bigger, without sacrificing our souls or selling out for the algorithm.

More places like that for the creative community would truly be valuable to all.

1 Easier before social media platforms started algorithmically penalizing posts that link beyond their walls.

2 No shade at all to Ghost, which we continue to happily use for our personal website. Our personal publishing stack: Ghost to host our website and Substack to send emails. This does require double-posting, but it’s a small price for the best parts of both platforms.

3 The core architecture underneath Metalabel is a data structure called “Decentralized Identifiers,” or DIDs. This is an open data format similar to the tooling underneath post-platform spaces like BlueSky that allows data to be interoperable and referenceable between platforms in a standard, open way. All existing Metalabel releases, accounts, and catalogs are architected as DIDs, meaning they can are capable of being embeddable and interactable with other services in the future.