This book is a financial experiment

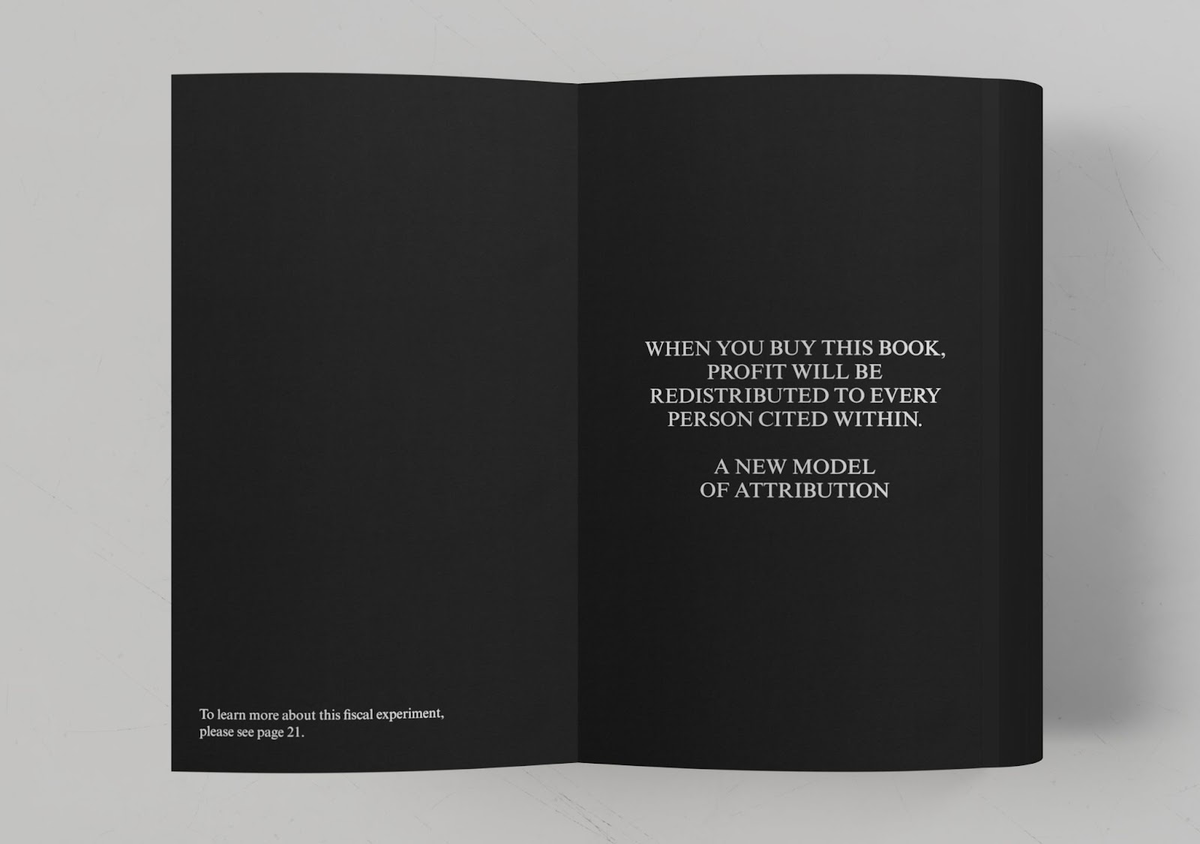

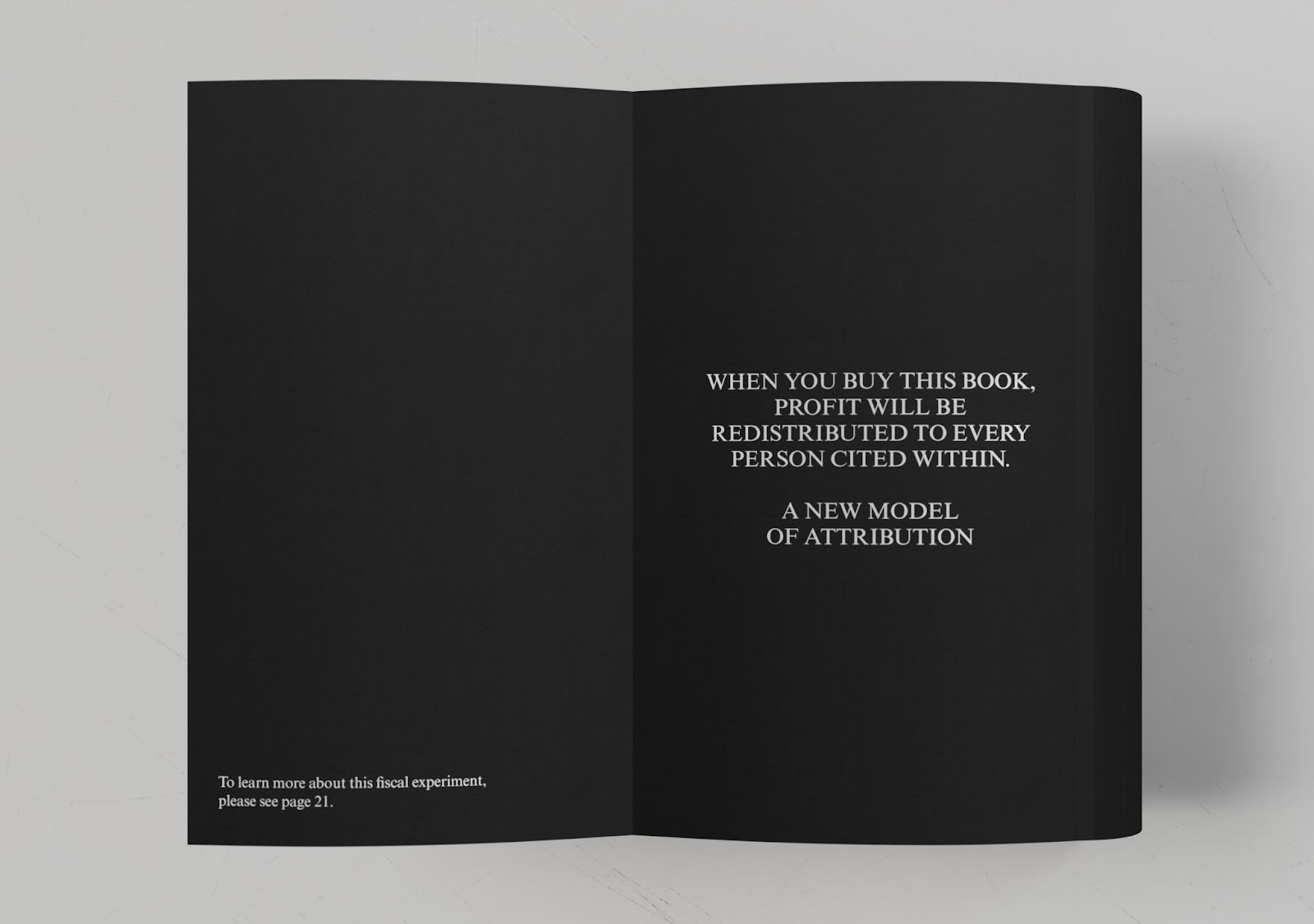

When you buy this book, profit will be redistributed to the people cited within

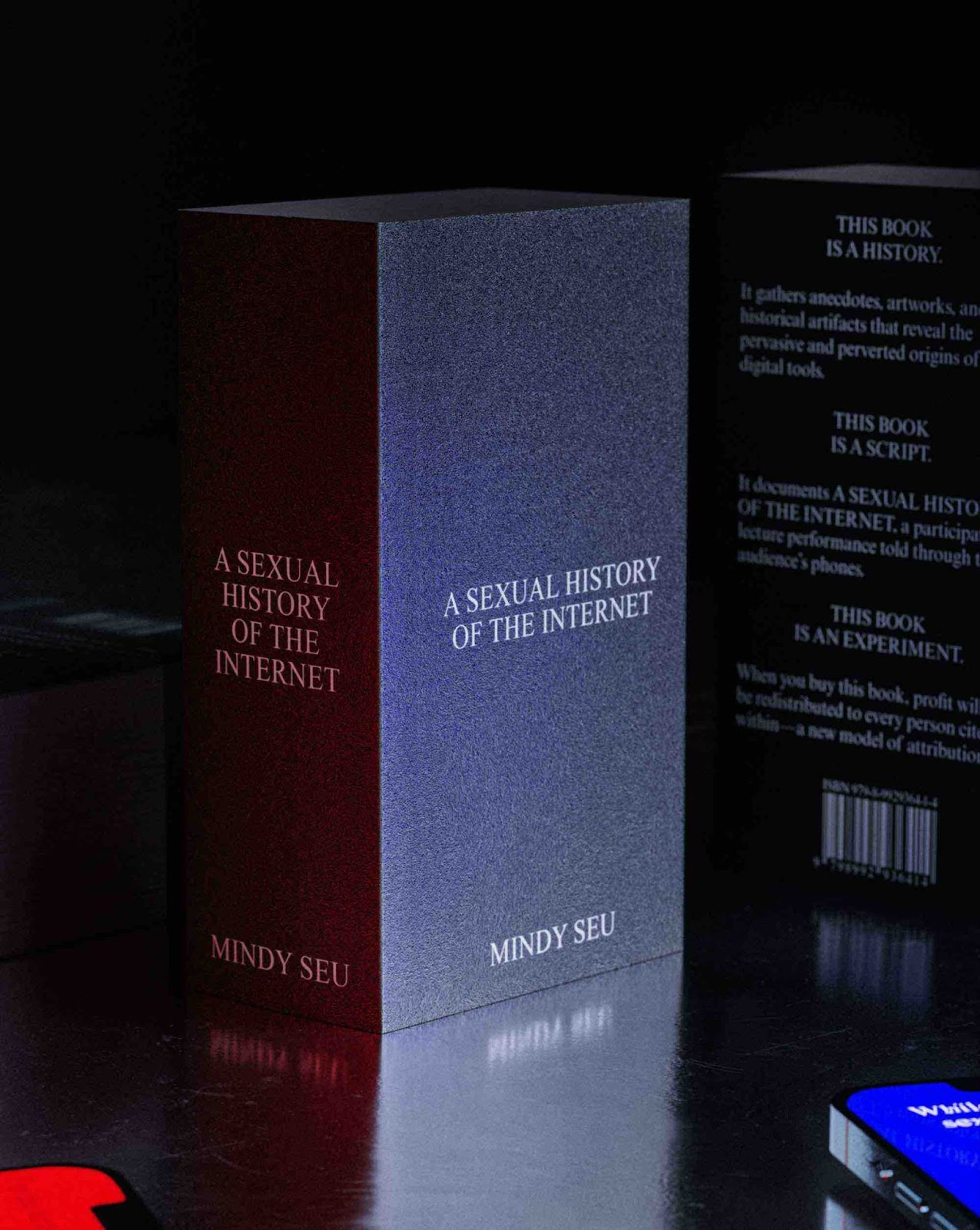

By Mindy Seu

This is an abbreviated excerpt from the introduction of the printed version of A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET. It has been edited for clarity. We’ve also included a numerical breakdown here that was not included in the book.

A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET is a polyvocal retelling of sexual technologies in five chapters. It’s less an abridged history and moreso a collection of experiences, anecdotes, and historical artifacts that reveal the pervasive and perverted origins of many of our digital tools. There are many great scholars of sextech history, and I can’t claim to be one of them, but I am one of its active enthusiasts, accomplices, and gatherers, alongside my research in internet art and activism.

A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET is a project in two parts: (1) a participatory lecture performance told through the audience’s phones and (2) an artist book.

A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET, the book, is a fiscal experiment of redistribution. In it, you’ll find citations1 by 46 people who have shaped my understanding of the internet, sex, and sexual technologies. When you buy this book, they will split a percentage of profits. Let’s call this experiment “Citational Splits.”

A common payment model for publishing looks like this: a publisher takes a majority cut of book profits for production, storage, shipping, etc. The author receives ~10%. Other members of the team (like editors, designers, lithographers, etc.) receive a fixed lump sum. This is how it worked with my first book, the CYBERFEMINISM INDEX, for which I chose a formal publishing process with a publisher (Inventory Press) and distributor (DAP).

With A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET, I wanted to test out something new. All books are publics, built from references, quotes, and ideas from others. Not only did I want to cite everyone, I wanted to develop a new model of citation. Let’s credit everyone. Let’s pay everyone.

Self-publishing seemed like the only viable option for this. And so, I turned to Yancey Strickler of Metalabel, an artist publishing platform that makes transparent a profit-splitting mechanism. With Metalabel, you can easily allocate payouts and percentages to members of the team (see Yancey’s case study “The economics of self-publishing a book on Metalabel”). I expanded on Metalabel’s splitting mechanism to create Citational Splits, a pool in which those cited will equally split 30% of profits, in perpetuity, including all future reprints.

Our profit split for A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET looks like this.

- 10% — Metalabel

- 60% — Team

- 30% — Citations

Our team includes:

- Author: Mindy Seu

- Collaborator: Julio Correa

- Designer: Laura Coombs

- Editor: Meg Miller

- Illustrator: Ven Qiu

- Metalabel: Yancey Strickler

Our citations include:

- Ali Na

- Allie Eve Knox

- Ana Voog

- Ani Liu

- Ann Hirsch

- Anna Uddenberg

- Arvida Byström

- Bogna Konior

- Candela Capitán

- Carol Leigh

- Danielle Blunt

- Douglas Engelbart

- Dragan Espenschied

- Emily Chang

- Esra Soraya Padgett

- Gabriella Garcia

- GynePunk

- Hacking//Hustling

- hannah baer

- Howard Rheingold

- Jennifer Kaye Ringley

- Kate D’Adamo

- Ken Knowlton

- Kristina Wong

- Lena Forsén

- Leon Harmon

- Liara Roux

- Linda Williams

- Livia Foldes

- Lorelei Lee

- McKenzie Wark

- Melanie Hoff

- Melissa Gira Grant

- Mistress Harley

- Qiujiang Levi Lu

- Rachel Kuo

- Sadie Plant

- Samantha Cole

- Sarah Friend

- Sinnamon Love

- Soda Jerk

- Theodor Holm Nelson

- Tina Horn

- VNS Matrix

- William Pietz

- Zahra Stardust

You’ll find their names near their respective quotes and images in the book and lecture performance, as well as the bibliography and “people cited” sections.

The financial overview looks like this:

Each book costs ~$12 to produce and ~$5 to ship.

5000 copies were printed; 4500 are for sale

Most sell for the market rate of $35, but many are sold to bookstores for the wholesale rate of $20.

Profit per book is ~$17.

Those in the Citation Pool equally split 30% of profits.

The more people opt in, the more each individual’s percentage decreases.

If someone opts out, their share is reallocated back to the others in the Citation Pool.

Of the 46 people who were cited:

27 opted in

4 reallocate their share

1 of these people initially opted in but then chose to reallocate because they are not able to use Metalabel. Metalabel uses the payment processor Stripe, and it is common, though unethical, for payment processors to ban sex workers from using their tools.

6 did not reply

5 are deceased

4 were unreachable

The 27 people who opted in will receive ~$0.19 per book. If all copies sell, each person will earn ~$850.

Each person will continue to receive splits in perpetuity for all future reprints.

Like all experiments, there are many variables at play. These numbers are estimates. There are several factors that might change this estimate. For example, our calculations use market-price sales, even though we’ll have a mix of sales that are market-price and wholesale-price. Or, we might not sell many copies of the book. Or, Trump’s volatile legislation on tariffs will impact shipping costs (this has already impacted our palette shipping for getting 3,000 books into the USA). Or, we might need to hire more contractors. Or, we might be able to make the book cheaper, which would increase everyone’s percentage. Etc! We’ve done our best to approximate these numbers, but it is a living distribution.

A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET is a proof-of-concept for Citational Splits, in which those who are cited get paid for the use of their work. It’s an example of how small-scale or artist-run projects could reevaluate a broken system and make a small attempt at repair through redistribution.

It’s important to note that this is also a proof-of-concept for intentional opt-in. As an author, I am intentionally citing specific people, and I am intentionally redistributing profit to them. (This also means I could withhold profit from someone that I am critiquing, for example). Each person cited received a breakdown of the potentials and pitfalls of this experiment. They are then intentionally opting-in to participate and receive payment, or they are intentionally opting-out to reallocate their fee to others. It’s a concept in line with models of redistribution like sliding scale or pay-it-forward, and directly in contrast with existing micropayment models focused on automation and scale, such as automatic micropayment-per-click or -view for creators (like Instagram), or automatic micropayment-per-click for the platform (like Google). Instead of a payment model that encourages the proliferation of the attention economy through clickbait, intentional opt-in means that we choose where our money goes.

There has never been a single mode of citational praxis — oral histories can be understood as community citations, while retweets, shares, and screenshots on social media are a form of social citations. But academic citations have perhaps the strongest association with the word, and thus “citation” still carries a connotation of formality, structure, and exclusion. This ethos is reinforced in ways so banal we hardly even recognize them: in the early days of search engines like Google, link ranking was modeled after academic citations; links were sorted based on the authority of the writer, in addition to the quantity of clicks. Some academic journals give more or less prominence to different media: books in print are considered more legitimizing than ephemeral media, like websites. Sites like Wikipedia only accept secondary sources, while primary sources are considered delegitimate.

Some histories benefit from these structures of exclusivity and authority. These methods of citations are useful in many ways, but they also uphold certain points of view. Which histories thrive in ephemerality, from primary sources, oral histories, and whisper networks? In The Cancer Journals, Audre Lorde wrote, “And yes I am completely self-referenced right now because it is the only translation I can trust…” I want to cite those without a textual record as well.

This book is documentation of a performance. It is a history of multiple “voices,” whose citations are read aloud by the audience; performance as re-citation. It reveals the perverted histories of technology that we are not often taught. It cites a range of artists, scholars, sex workers, and the like. It connects citations with a micropayment model that redistributes funds, introducing a new model of attribution. This book doesn’t play by the rules of a book, and that frees it up to new possibilities. And this book, like all books, is a public; as readers, you are invited to take part.

Thank you to all of the friends and collaborators who made this possible:

Artist, Author: Mindy Seu

Designer: Laura Coombs

Editor: Meg Miller

Collaborator: Julio Correa

Illustrator: Ven Qiu

Timecodes Scripting: Jon Gacnik

Videographer: Gabriel Noguez

3D Artist: Tom Hancocks

Website Support: Charles Broskoski

Metalabel: Yancey Strickler, Lena Imamura

Consultant: Gia Kuan Consulting

Printer: DZA

The Instagram-Stories-as-Lecture format was first conceived of by Julio Correa in Seu’s Lecture Performance studio course (Fall 2023) at Yale School of Art. Seu further developed this format, in collaboration with Correa, for A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET. This was then translated into a book in collaboration with Laura Coombs.

We’re using an expanded definition of “citations”. Some are textual citations. Others are verbal quotes that I transcribed and then confirmed with the person. This also includes all of our images; we received image permissions from each artist, but also included them in the Citation Pool. ↩